African American Maritime History Series #8: The Maritime Underground Railroad

The World’s first global economy was fueled by maritime commerce which for the first time in Earth’s history fully linked the people and countries that surrounded the Atlantic Ocean in a ecosystem of trade, conquest, settlement, and enslavement. Europeans carved vast colonies out of land where people had lived for thousands of years in the Americas. From gold to sugar, the resources of these conquests transformed European societies. The transatlantic trade of enslaved humans carried millions of Africans westward to lives of labor and woe. Ships and sailors created a complex new world with maritime commerce at its core.

The World’s first global economy was fueled by maritime commerce which for the first time in Earth’s history fully linked the people and countries that surrounded the Atlantic Ocean in a ecosystem of trade, conquest, settlement, and enslavement.

Europeans carved vast colonies out of land where people had lived for thousands of years in the Americas. From gold to sugar, the resources of these conquests transformed European societies. The transatlantic trade of enslaved humans carried millions of Africans westward to lives of labor and woe. Ships and sailors created a complex new world with maritime commerce at its core.

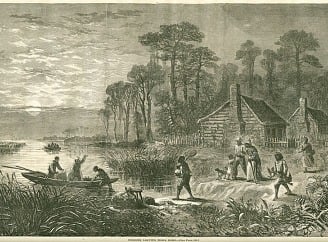

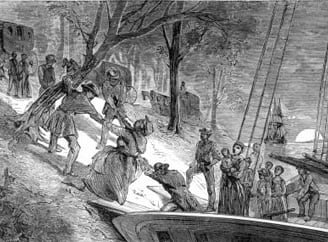

As a result of the intra-coastal maritime commerce that existed between the thirteen colonies on the North American Atlantic coast, the Maritime Underground Railroad was birthed. The Maritime Underground Railroad consisted of a network of people who aided enslaved freedom seekers to escape by water vessels from the southern United States to freedom in the North and Canada. Enslaved people escaped aboard the thousands of ships that did business between the North and South sailing regularly up and down the Atlantic coast between colonial port cities. A clandestine society of enslaved port workers directed fugitives to the ships and freed Black crewmen secreted them on board.It was not surprising that enslaved people were able to use waterways for their escape. All the labor to move goods and products along the waterways of the South was supplied by enslaved people. They were the labor force on the waterfront of the entire Southern Seaboard utilizing every little inlet, port city, tidal waterway and river in route to the ports for loading onto larger ocean-going vessels to take them to market.

Wilbur Siebert, one of the first historians to extensively research the Underground Railroad, wrote in his 1898 book, “The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom,” “The advantages of escape by boat were early discerned by the enslaved living near the coast or along inland rivers. Vessels engaged in our coastwise trade became more or less involved in transporting freedom seekers from Southern ports to Northern soil.”

Additional evidence of the importance of coastal ports to the overall Underground Railroad system was William Still’s published 1872 collection of accounts of escapes from enslavement, “The Underground Railroad,” which had an overwhelming number of stories focusing on fleeing in ships traveling along the East Coast.

Further, in the early 1800s, enslaved Black people in Florida and other regions of the deep South were hundreds of miles from border states like Maryland and Kentucky and thousands of miles away from the "promised land" of British Canada, making their options and odds for a successful escape close to zero.

The preponderance of the attention on the Underground Railroad story typically has been fixated on terrestrial escapes. However, newer historical data has pointed to an overwhelming amount of evidence shifting attention to the sea as a major component centric to the freedom seeking narrative that had been typically shared. Present evidence shows that by a considerable margin documented escapes using terrestrial routes of the Underground Railroad were typically from slaveholding states to the adjacent free states. Very rarely was it practical for enslaved persons to escape over land. Mainly, the territory was unknown to them.

Further, the lack of proper shoes, clothing and the logistics of organizing shelter and food while traveling primarily at night in hostile territories with organized patrols would have been extremely difficult, if not impossible, over long distances. Most documented successful overland escapes began within a few days walk of a body of water where water transportation was available or very near states where enslavement was banned.

Southern legislatures, starting with South Carolina, passed numerous Negro Seamen’s Acts from 1822 into the 1840s because they were convinced that enslaved persons were escaping regularly aboard northern bound vessels. The Negro Seamen’s Acts were intended to limit the free movement of northern freed Black crewmen in southern ports. They presumed that the freed Black northern crewman were enticing the enslaved in the southern ports to escape. Nonetheless, freed Blacks continued to work as crew on ships engaged in the coastal commerce.

In 1526 the Spanish had brought the first enslaved Africans to what would later become America's Southern shores – nearly 100 years before the British colonized North America. They labored in the fields and groves. In an effort to destabilize British colonies farther north, Spain began offering asylum to enslaved freedom seekers in 1693, but only if they converted to Catholicism and performed four years of military service.

That enticing policy turned Spanish Florida into a haven for enslaved runaways and led to the birth of the first sanctioned free black settlement – Fort Mose – in what would ultimately become the United States.

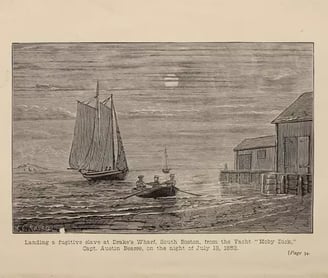

This escape route heading south into Spanish Florida was called the Saltwater Underground Railroad. Believed to have operated between 1821 and 1861, the Saltwater Underground Railroad refers to the coastal escape route followed by enslaved freedom seekers into the British-controlled Bahamas. An underground network from Georgia, North and South Carolina, coastal Alabama, and Mississippi, also extended into Spanish Florida.

From there, some paid for their passage on Bahamian vessels, while others made their way across the perilous Atlantic in dugout canoes and small boats. Once out to sea, under the cover of night, they faced unimaginable unknowns: unpredictable weather and storms, possible recapture by slave hunters, assault by pirates, and foreboding, deep, dark waters.

Situated 150 miles off the coast of Miami, Florida, the islands that comprise the Bahamas became a viable destination for several reasons. For one, in 1825 the British government had declared that anyone reaching British territory was considered free, regardless of their prior status. In 1834, slavery was abolished in all British territories which included the Bahamas. Free Blacks in the Bahamas could get married, own land, and pursue an education – basic human rights that were inconceivable for enslaved human beings in the antebellum South. And because the population was mainly Black, it was easy for Black freedom seekers to assimilate into a diverse community of native Bahamians, along with Bahamian descendants of enslaved Africans, Africans and maroons, also called "Black Seminoles," who were runaways from the deep South and Gulf coast who originally had sought refuge with the Creek Native Americans in Florida.

Despite the dangers and variable odds of success, a high proportion of freedom seekers made their escape from slavery on the Maritime Underground Railroad and took their first steps on free soil in a northern port city or by means of the Saltwater Underground Railroad.

Kim Cliett Long, Ed.D., FRSM, FRSPH, FRGS

Sources

Calabretta, Fred. "The Picture of Antoine DeSant." The Log of Mystic Seaport Volume 44 No. 4, Spring 1993.Rediker, Marcus. The Amistad Rebellion: An Atlantic Odyssey of Slavery and Freedom. New York: Viking, 2012.Zeinert, Karen. The Amistad Slave Revolt and American Abolition. North Haven, CT: Linnet Books, 1997.Cable, Mary. Black Odyssey: The Case of the Slave Ship Amistad. New York: Viking Press, 1971.Jones, Howard. Mutiny on the Amistad: The Saga of a Slave Revolt and Its Impact on American Abolition, Law, and Diplomacy. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.National Archives. "Teaching With Documents: The Amistad Case." Accessed July 11, 2013. http://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/amistad/.Atlantic Slave Trade. 6 February 2014, 09:42-UTC. In Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Commons Inc. Encyclopedia on-line. Available from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atlantic_slave_trade. Retrieved 1 August 2013.The Institute of Black Invention and Technology. "Lewis Temple: The Temple Toggle Iron." Inventor of the Month. Last Modified 2012. Accessed February 20, 2014. http://www.tibit.biz/inventor-2007-8.htmNew Bedford Historical Society. "Lewis Temple." Important Figures. Last Modified 2007. Accessed February 20, 2014. http://www.nbhistoricalsociety.org/lewistemple.html

Related Literature

Douglass, Frederick, James McCune Smith, and Gerrit Smith. My Bondage and My Freedom. New York: Dover Publications, 1969.Washington, Booker T. Up From Slavery; An Autobiography. New York: Doubleday, Page & Co, 1901.Gordinier, Glenn S. ed. Gender, Race, Ethnicity and Power in Maritime America: Papers from the Conference Held at Mystic Seaport, September 2006. Mystic: Mystic Seaport Museum, Inc., 2008.Bolster, W. Jeffrey. Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998.McKissack, Pat, and Sanna Stanley. Amistad: The Story of a Slave Ship. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 2005.Chambers, Veronica, and Paul Lee. Amistad Rising: A Story of Freedom. San Diego: Harcourt Brace, 1998.Myers, Walter Dean. Amistad: A Long Road to Freedom. New York: Dutton Children's Books, 1998.