African American Maritime History Series #4: Maritime Work Songs

Historically, along the African coast, there was a requiem-like cadence in all their songs, while at work or paddling their canoes to and from shore, they kept time to the music. On Southern plantations, it was heard also, and in the African melodies everywhere, plaintive, and melodious, sad, and earnest. African workers, both in Africa and in America, were widely noted to sing while working. European observers found African work-singers remarkable because work songs were foreign to European culture. Such references begin to appear in the late 18th century, where the cliché is seen developing that Africans "could not" work without singing. For example, an observer in Martinique in 1806 wrote, "The negroes have a di!erent air and words for every kind of labor; sometimes they sing, and their motions, even while cultivating the ground, keep time to the music."

So, while the depth of the African American work song tradition is now recognized, in the early 19th century this music stood in stark contrast to the rarity of such traditions among European Americans. Thus, while European sailors had learned short chants to use for certain kinds of labor, the paradigm of a comprehensive system of developed work songs for most tasks was contributed by the direct involvement of or through the imitation of African Americans. The improvisatory singing and community participation commonly found in African music produced call and response and repetitive chorus structures. It also encouraged individual expression, where singers freely injected utterances, and varied vocal timbres to produce groans, shrills, moans, wails, and screams that convey emotions and sounds of everyday life. Additionally, this approach produced verses harmony, the simultaneous rendering of slightly di!erent versions of the same melody by two or more performers. The centrality of dance in music-making activities established the hierarchy of rhythm over melody and the dominance of polyrhythmic structures, i.e. the layering of contrasting rhythms.

Comparing the rhythmic component of Black and European music, theorist Earl Stewart explains that nearly every traditional Western classical style employs syncopation; in African American music, it virtually defines style as illustrated in ragtime. Syncopation is the shifting of accent from standard European stressed beats to atypical stress points in the measure. During the first half of the 19th century, some of the songs African Americans sang began to appear in use for shipboard tasks among European Americans. Eventually these songs were naturalized by seamen into the various European cultures from which the sailors originated. For the enslaved Africans, music – rhythm in particular – helped forge a common musical awareness. With the understanding that organized sound could be an e!ective tool for communication, they created a world of sound and rhythm to chant, sing and shout about their conditions. Music was not a singular act but permeated every aspect of daily life. In time, versions of these rhythms were attached to work songs, field hollers and street cries, many of which were accompanied by dance. The creators of these forms drew from an African cultural inventory that favored communal participation and call and response singing wherein a leader presented a musical call that was answered by a group response.

Maritime Work Songs

The evolution of African work songs out on the Atlantic among the primarily European crews became commonly known as sea chanteys (or shanties) which were sung to help fishermen and sailors pace their work. The many di!erent types of shanties vary according to the desired rhythm and nature of the work.

Writers have characterized the origin of shanties or perhaps a revival in shanties, as William Main Doerflinger theorized as belonging to an era immediately following the War of 1812 and up to the American Civil War. This was a time when there was relative peace on the seas and shipping was flourishing. Packet ships carried cargo and passengers on fixed schedules across the globe. Packet ships were larger and yet sailed with fewer crew than vessels of earlier eras, in addition to the fact that they were expected on strict schedules. These requirements called for an e!icient and disciplined use of human labor. American vessels, especially, gained reputations for cruelty as o!icers demanded high results from their crew. The shanties of the 19th century could be characterized as a sort of new "technology" adopted by sailors to adapt to this way of shipboard life.

The working of cargo was performed by stevedores to the accompaniment of shanties, for example in the tradition of the Georgia Sea Island Singers of St. Simons Island, Georgia. They used such shanties as "Knock a Man Down" (a variation of "Blow the Man Down") to load heavy timber. The category of menhaden shanties refers to work songs used on menhaden fishing boats, sung while pulling up the purse-seine nets. The musical forms, and consequently the repertoire, of menhaden shanties di!er significantly from the deep-water shanties, most noticeably in the fact that the workers "pull" in between rather than concurrently.

The sea and other water ways such as large lakes, long rivers, and wide bays, have inspired songs for centuries. Maritime music plays a major role in life on the water, through its ability to entertain, motivate, and pace seamen in their work. Sailors and fishermen sing rhythmic songs called shanties while pulling in nets, hauling anchors, and setting sails in unison. Songs are composed to commemorate battles at sea, pirate attacks, or storms. Some maritime songs celebrate particular bodies of water dear to a singer/songwriter's heart; others remind seafarers who and what waits for them on land. The development and use of African American maritime music aligns with the use of work songs in the rice, indigo, tobacco, and cotton fields. This work music developed tolerance for harsh working conditions; provided rhythm for organizing and completing tasks; created a system of communication; and, provided entertainment to counteract an otherwise dismal environment.

The Maritime Historical Backdrop

Historians have understood the shaping impact of the maritime world on North American slavery for some time. Virtually every American history survey text includes maps showing the concentration of enslaved people along the oceans and inland waterways of antebellum America. From the earliest days of slavery until emancipation, enslaved people lived and worked in close proximity to the water transportation networks. Given the significance of water commerce to the history and sustainability of slavery, it is remarkable that historians have been slow to conceptualize the meaning of this water association for African Americans.

In the voluminous literature on slavery historians have not addressed the basic question: how did the Atlantic maritime world shape the experience of North American enslaved and freed people? David S. Cecelski's history of maritime North Carolina is the first full-scale study to address this important matter. His answers highlight the remarkable opportunities for the enslaved to take independent action in the maritime world. Without underplaying the harshness of the slavery experience, he argues that enslaved and free Black maritime workers provided the enslaved community with material subsistence and possibilities for liberty.

One of the key themes of the book is that the experience of maritime work varied. While a growing body of scholarship focuses on black sailors on the high seas, Cecelski's subjects work in a variety of jobs, most of which are closer to shore. In addition to revealing the lives of black schooner and lightermen, Cecelski discusses canal building, bateaux boating, rafting, levee work, and various kinds of fishing. Cecelski shows the di!iculty of this work. His chapter on canal building makes the reader realize the horror of slavery. Wading in waist deep water in the swamps of coastal North Carolina, the enslaved were expected to clear trees, logs, and a jungle of vegetation, all the while evading insects and poisonous snakes. At the end of the day, the enslaved often slept unprotected in the mud. Even fishing was extremely arduous.

While Cecelski illustrates the freeing mobility of fishermen and the significant impact of fish on the larger enslaved community's diet, he also shows the dangers of diving for oysters in the dead of winter. In the herring, rockfish, and shad fisheries, which flourished seasonally in the estuaries of the coast, the enslaved dove into murky waters to clear river bottoms of branches and stumps in order to create clear pathways for their nets. When manual methods failed, they used dangerous explosives. Cecelski stresses the diversity of the African American maritime pursuits, but he shows that a culture of resistance connected them all. This resistant culture was shaped by a fluid network of contacts that connected the various sectors of the maritime world to each other and to shoreside enslaved persons. Watermen were inherently worldly, even if they were just local fishermen. Ports in coastal cities provided a meeting place for the enslaved hungry for news and information. It was within this maritime network that contributed to the success of escapes by the enslaved. These enslaved escape networks connected plantations and coastal cities of the Atlantic South which established the Maritime Underground Railroad.

Black sailors helped runaways stow-away to freedom, risking imprisonment to challenge slavery. Cecelski attempts to trace this culture of resistance into the eras of the Civil War and Reconstruction. His chapter on the war years brilliantly argues that the enslaved waterman were important in bringing about Union victory and emancipation. By guiding federal vessels in occupied coastal Southern port cities, serving in the Union navy, and spreading word of federal invasions inland, Cecelski shows the continued role of the maritime culture of resistance. There is much more work to be done to examine and unfold the many contributions of Africans and African Americans to the building of America using the lens of maritime history and culture in the watery Atlantic World of the thirteen colonies. The Southern Lowcountry cultural landscape was largely fueled by African and African American maritime labor. Because the labor was provided by enslaved people there is less documentation than that of the freed people in the Northern Atlantic colonies.

Kim Cliett Long, Ed.D., FRSM, FRSPH

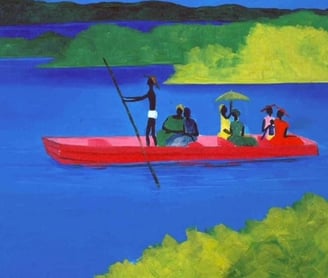

Artwork provided by Jonathan Green (TM)

Support for this series provided by: